D-Day Artist Orville Fisher

Art In Action – D-Day Artist Orville Fisher

As a Canadian and an artist, I have many things to be grateful for in this life. Many of us are familiar with the exceptional art of renowned Canadian painter Alex Colville, a war artist who created some of the most iconic paintings of Canada at war. As we approach the 80th anniversary of D-Day, I want to highlight another artist who may not be as well known today, D-Day Artist Orville Fisher.

On D-Day, 6 June 1944, Canadians landed on the beaches of Normandy and played a crucial role in the liberation of Western Europe. The success of this immense operation, the largest seaborne assault in history, was made possible by weeks of intensive preparation, in which Canadians were key players. Much has been written about the significant role the Canadian Army played in the D-Day invasion, and rightly so. Orville Fisher’s paintings of the Second World War constitute one of the most complete records of Canada’s day-to-day role in that conflict. Perhaps his chief claim to fame is that he was the only Allied war artist to land in Normandy on D-Day. This achievement is all the more extraordinary given the fact that he almost never made it overseas in the first place. The hundreds of works he completed, now in the collection of the Canadian War Museum, reveal an artist whose interests lay in the action of war rather than in the ravaged landscapes that typified First World War art.

Fisher began working as a service artist with the Canadian Army in February 1942 and became an official war artist a year later. He did not return to civilian life until July 1946. As a war artist, Fisher was determined and creative. In preparation for the D-Day invasion, he strapped tiny waterproof pads of paper to his wrist. After racing up the beach from his landing craft, Fisher made rapid, on-the-spot sketches using perfectly dry materials, capturing the battle unfolding around him. Later, he created larger watercolor paintings away from the battlefront. Unlike fellow war artist Charles Comfort’s reconstruction of the August 1942 Dieppe Raid, which was created four years after the event in the peace and security of a studio, Fisher’s *D-Day – The Assault* was based on his real-life experience, replete with all the turmoil and blood. Attached to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, Fisher landed on the beach at Courseulles-sur-Mer. The first 20 minutes of Steven Spielberg’s film *Saving Private Ryan* arguably re-creates the artist’s D-Day experience in all its horror.

Before the war, Fisher worked largely as a painter of murals for buildings and churches in the Vancouver area, in partnership with fellow future official war artists Paul Goranson and E.J. Hughes. Upon learning that war had been declared in September 1939, the trio determined that their artistic skills should be put to use in some official military capacity. The example of the First World War art program, the Canadian War Memorials, was their inspiration. Within two weeks of the outbreak of war, they wrote to the director of the National Gallery of Canada, H.O. McCurry, seeking employment as war artists. McCurry forwarded their applications to the Department of Defence in October, but at that time, the military had made no provision for employing artists.

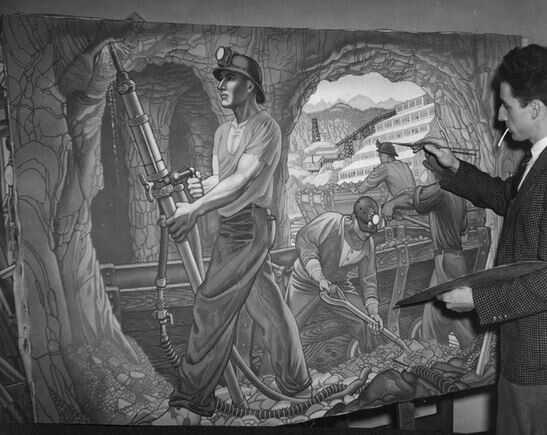

Artist Orville Fisher at work on the mural he did with E.J. Hughes and Paul Goranson for the British Columbia section of the Western States Building at the San Francisco World’s Fair in 1939. The photo is dated Feb. 3, 1939, and was taken by San Francisco photographer J.K. Piggott. Vancouver Sun

With no response forthcoming, Fisher joined the Royal Canadian Engineers in August 1940. However, his earlier correspondence appears to have come to the attention of the director of the Historical Section in Ottawa, A. Fortescue Duguid, who began to make use of Fisher and Hughes as war artists in Ottawa, hoping a more serious program might develop. “The employment of selected members of the Canadian Army (Active) on the pictorial recording of Canadian participation in the current war is contemplated,” Duguid wrote to McCurry in March 1941. “For some time past two artists, Sergeant E.J. Hughes and Sapper O.N. Fisher have been under instruction here with a view to testing and improving their capacity to function effectively as war artists in the field.” Two years later, with a war artist scheme just announced, Fisher and artist Jack Shadbolt were still pleading with McCurry for a chance to record the action. “We are both determined to make every reasonable effort to be in a position to work effectively,” Shadbolt wrote on behalf of them both.

Artist E.J. Hughes at work on the mural he did with Orville Fisher and Paul Goranson for the San Francisco World’s Fair in 1939. Vancouver Sun

Only one day after this letter was written, on 5 February 1943, the Canadian War Artists’ Control Committee in Ottawa recommended the appointment of Fisher as an official war artist. It was still not all smooth sailing. Fisher was ready to go to England in September 1943 when the Canadian High Commissioner in London, Vincent Massey, wrote to McCurry that he and his advisory committee did not think Fisher was “qualified to perform the duties proposed.” Massey’s assessment was based on reproductions of the artist’s work that he had been sent. The Army’s historical section in Ottawa responded that “his talents [did] deserve employment.” McCurry, Chairman of the War Artists Control Committee in Ottawa, stood by the original February appointment, and despite Massey’s reservations, Fisher set sail for England. We will probably never know whether he was aware of how close he had come to failing in his four-year goal. Suffice it to say that the energy and commitment he had put towards becoming a war artist were now directed at producing a war record that not only told of the achievements of Canadians but also advanced his own art. By the end, he had reversed the negative opinions of 1943.

Untitled, Orville Fisher’s mural from 1957 featuring the figure of Mercury, god of messages and glad tidings, inside the post office building at 349 West Georgia Street, by the Homer Street entrance.

From D-Day Artist Orville Fisher, to Vimy100.

If you enjoyed this post, you might enjoy this story of making a painting celebrating a meeting at Vimy 100.